Our farm has a singular focus. We raise sheep for their wool so handspinners can use our fleeces to make lovely, soft, elastic yarn.

|

| We raise sheep for their wool |

So when we harvest the wool from our sheep, we take very particular care to ensure it is harvested in a way that is optimized for hand processing the wool for spinning into yarn.

|

| Freshly sheared fleece from our Elara |

This means making sure it is clean and free of neps or second cuts. These faults that occur during the harvesting of fleeces diminish the efficiency for handspinners so we do everything we can to prevent them.

We use two methods to harvest our fleeces. One is shearing, where our professional shearer travels from Massachusetts to our farm for a day of shearing sheep, always in the spring after the cold weather has passed and the sheep don’t need their fleeces to stay warm.

|

| Our shearer is an expert at shearing fleeces for handspinners |

Shearing is fast work, we usually shear around 40 of the sheep in about 3 hours or less. It is safe for the sheep, and is a great way to get the wool off the sheep quickly. There is skill involved to ensure the fleece is good quality for handspinners - making sure the staple is preserved and the fleece all comes off in one piece. The only issue with shearing is that there is an unpreventable chance you will get little bits of residual wool that can’t be used by the handspinner, and in fact, can be a bit of a nuisance when prepping and spinning the wool.

|

| An example of a fleece with neps due to the rise |

This happens regardless of the skill level of the shearer and is more the result of shearing a sheep that has a break or a rise in their fleece. This condition is very unique to a few breeds of sheep, and shetlands are one of those breeds that have this natural break in their fleece.

For sheep with a rise, or break, in the fleece, the ideal method for harvesting wool is a process called “Rooing”, which is what this blog post is all about.

Shetland sheep have a unique trait where they reach a point in their fleece where there is a break in the staple. This break is also known as the rise.

|

| A very good example of the break in the fleece |

When they reach the rise, always in the spring, it is time to harvest their fleeces with a process called rooing. Rooing is where you pluck the wool from the sheep, taking advantage of the weak spot. This harvesting method is an alternative to shearing, which doesn’t require a break in the staple, so you can shear sheep anytime you like.

|

| I love rooing my sheep! |

The rise will occur at different times with different sheep. Some sheep “hit the rise” very early in the season, say February. Others hit it later in early summer. And some of our shetlands never even have a well defined rise, these will always be sheared by our professional shearer all on the same day. I have tried to come up with some sort of correlation to predict who will have a good weak rise, but haven’t yet. So not sure if it is the fineness of the fleece, staple length, crimp or some other trait that could be linked to having a good, weak rise.

Another thing I’ve noticed over the years is that some sheep roo really easily at the britch, which is the area around their tail and back legs, but less so as you get closer to the neck. Before shearing day I actually check all the ewes I am thinking of rooing to make absolutely sure they are going to roo easily at the neck and side, in addition to the britch.

|

| Rooing the britch area |

I use the term “weak rise” to indicate that the fleece will come off the sheep really easily because the break in the staple is significant. Sometimes the rise is weaker some years over others with the same sheep. I’ve noticed that if a ewe carried a lamb over the winter, they are very much more likely to have a weak rise. Mrs Hughes was an example - the year she had lambs she was very easy to roo, the year she didn’t have lambs I couldn’t get the wool off and had to actually cut her fleece of with scissors (I don’t have shearing clippers, nor do I know how to use them!). Sadly her fleece that year was pretty mangled, but the positive side is I think this was when I figured out how to make my “bumbly” yarn as her fleece has a lot of shorter curly bits that are perfect for this type of spinning.

|

| Newly Invented Bumbly Yarn from Mrs Hughes Disaster Fleece |

Also, her fleece the following year had a lot of irregularity at the tip due to the hybrid method I had to use to harvest her fleece.

|

| Can you see the extra tip? That came from her prior years growth that I couldn't get off. |

This year I had 74 sheep with fleeces to harvest. I sheared 42 of them, and am in the process of rooing the balance. Roo’d fleeces are really nice to process for handspinning as they don’t have any second cuts or neps from the clippers, and you can also determine what the exact staple length is for each sheep.

|

| The underside of a rood fleece is just perfection |

This is important information for breeding as we want ewes with longer staple length to increase our wool yield. Our shetlands have staple lengths from 1 “ up to 4” unstretched. If you stretch the staple, you can get an additional 1.5 inches usually because our wool is so very crimpy.

|

| A typical lock from our sheep |

I coat my ewes so the wool under the coat is nice and clean and free of VM.

|

| Coated ewes on pasture |

VM is short for vegetative matter, bits of hay and poo that embed in the wool and make it difficult to produce a nice clean skein of yarn. The wool outside of the coat is usually very dirty and full of vm.

|

| Neck wool loaded with "VM" |

And ewes that are 1 year old (yearlings) have the most amount of VM as they are smaller than the adults, and the hay tends to fall from the adults mouths into the back of the neck of the younger, smaller sheep.

|

| Yearling ewe on right, adult with ripped coat - can see the size difference |

So the wool from the roo’d sheep is offered as full raw fleeces for the wool under the coat. The neck, britch and belly wool goes into a pooled bag of wool, sorted by color for being made into combed top by my fiber processing mill.

|

| Skirtings, ram fleeces and older ewes wool is used to make our combed top |

I don’t coat my rams as I have concerns that they might get tangled in the back leg straps, which would make them vulnerable to attack from other rams. Ram behavior is very different from ewe behavior, and we try to minimize situations where rams would harm each other.

|

| Rams ready to be roo'd |

I try to keep myself to rooing one sheep a day. Many times I complete a ewe, and then really feel like I want to tackle another one. But the problem is many times at about 25% into my second ewe, my hands start to get very tired and sore, because the motion is very repetitive. Also, I get blisters and wear on certain parts of my fingers that get exposed to a lot of pressure during the process. Towards the end of rooing season, I take to wearing wrist braces and icing down my hands at the end of the day. When rooing a sheep, you really have to finish what you start. This is because you want the fleece to be all one piece, or ½ as is the case with a roo’d fleece.

I have a sheep stand with a neck brace that works really well for rooing.

|

| Sheep Stand is a great piece of equipment |

It has two removable sides which I make use of to keep the ewe from falling from the stand, and they also make very nice holders for the bag that I use to catch up the wool. I have received feedback that the stand appears to be cruel to the sheep because it’s head is immobilized on a frame. The fact is I have tried all sorts of ways to set the sheep up to make for a safe and efficient rooing session. I haltered them and tied them to a post, laid them on the ground, held them on my lap as I attempted to roo them. My conclusion is that the stand method results in a faster session, with less injury to me and to the sheep, and the fleece doesn’t get damaged by flailing legs or debris. And the sheep learn over time that the stand isn’t bad, just part of their routine that they just endure.

I have two bags at the ready before I start, and I make sure they are nicely opened and ready to receive wool. You don’t want to be cracking and snapping a plastic bag one handed with a ewe on the stand and lovely wool in the other hand, so have it ready to go before you start. I also make sure I take a quick photo of the ear tag of the ewe so I can create an index card that goes in the bag after i have finished.

|

| Tag# 1475 is our Janet - a lamb from last year |

I collect all the dirty wool first and put it in a bag. This is wool from the neck, belly, britch and legs. I do this with the coat still on so the coated wool doesn’t get all dirty. Plus, if you are rooing the side, it is difficult to know when you have reached the dirty wool toward the belly, especially if you are on the opposite side of the ewe looking over her back, which is my method. So I remove all the dirty wool first, and put in a separate bag.

|

| Wool on left is uncoated parts, right is under the coat - these are from the same ewe. |

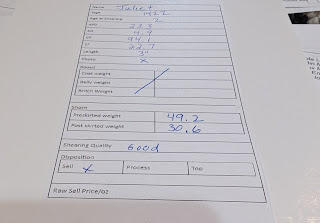

I will weigh this wool and note it on the sheep’s information card for that year, so I can get a yield number, which I use in breeding decisions. Yield is important, I want ewes that have minimal britch wool and more wool under the coat since our focus is producing fleeces for handspinners as opposed to mill processed combed top.

|

| One side of the info card on Juliet - other side is a copy of her micron report. |

The combed top is nice, but we look at it as sort of a by product to the premium product which is the raw fleeces.

Once I have the ewe secured on the stand, I will start to remove the wool that is outside the coat. This includes her britch wool, (which is the wool around her tail), her belly wool, the wool on her legs and her neck wool. If her neck wool is particularly nice, I will hold on to it and process it myself. Otherwise, it will all go into a pooled bag of britch and ram wool, sorted by color, destined for the mill to be made into combed top. Then I remove her coat and start rooing down her spine, from the neck to the tail.

|

| I start rooing along the backbone to start |

This creates a separation of the two halves of the marketable fleece. Then I start working from the top down, moving along her body so as not to concentrate the stimulation on one part of her side for too long. It doesn’t hurt them, but I am pretty sure it irritates some of them, so I try to dissipate the stimulation as I go. I also change my hand position and alternate hands frequently so as to minimize repetitive motion.

|

| Rooing is a workout for your hands and forearms |

|

| I use the rail to protect the fleece |

During the process, I try to figure out what the ewe likes as I am working on her. So if she responds well to belly scratches, she gets them intermittently during the session. Or a cheek rub, chest massage or tapping noses.

|

| Janet liked cheek scratches! |

Not all sheep are the same and all like to be comforted in different ways. In fact, I just roo’d a lamb named Lucia, and when I tried to scratch her cheek she nipped at me, but she liked it when I rubbed her belly! When I am working on the wool around her head I like to rest my head on hers if she likes it, it is a nice chance for intimacy between us, like how a mother sheep touches the lambs with her head.

|

| Rooing your sheep is an opportunity to show your sheep how much you love them! |

|

| All finished and ready to get back with the flock |

The reason careful reintroduction is important is because sheep flocks operate with a very clear hierarchy of power. There is the flock leader - she/he gets the best spot to sleep, is left alone at feeding time, and pretty much everyone steers clear of the flock leader. Then the ranking goes down from there all the way to the flock weakling who knows to get out of everyone’s way and if she/he doesn’t they will get knocked around. Every so often you will see middle ranking sheep decide it is time for a shift in the ranking, and there will be fights until it is resolved - which happens when one of the sheep backs down from the altercation. Once one of the sheep backs off, all is fine and dandy, no more fighting and everything settles down. Usually within a few minutes, but I have seen a couple ewes go at it hatefully for a couple of days. All of the sheep in the flock know the ranking, and are able to identify each sheep and her rank based only on appearance and smell. So, when you remove the coat and shear or roo a sheep and then send him/her back into the flock, that sheep is considered new and has to regain its position as if it was a new sheep being introduced into the flock.

|

| "You smell funny. Do I know you?" |

On shearing day, this results in absolute mayhem as a “new” sheep is introduced to a flock of “new” ewes every 7 minutes or so. Much more so with rams than with the ewes - we have had rams die as a result of the violent work they do to establish their rank after shearing.

|

| Chaotic introduction on shearing day |

So as I roo only one sheep per day, when that ewe gets sent back into the flock I want to give her the ability to have plenty of space to escape any possible aggression as she tries to find her spot in the ranking.

After the sheep has been released and I am happy that she is blending back in with her flock, I bag up the fleece from under the coat in one plastic bag, and the belly/britch/neck wool in another bag. I use plastic kitchen garbage bags, with colored ties as I use the ties to identify the fleeces. This year the sheared fleeces have a blue tie and the roo’d fleeces have a red tie. I then weigh both and record the weights on individual sheep cards where I compile the information on their fleeces including micron data, staple length, weights and any notes I may deem fit to record. I use these cards for a lot of things, Primarily I use them to upload information for the fleece auction, when I am creating the data sheets for the fleeces, and reference when making breeding decisions. I also enter the weights into a spreadsheet for all the fleeces I’ve harvested so I can calculate yields, sort by various traits like staple length or shearing quality and have as a reference during the year.

Roo’d fleeces are prized by handspinners because of the pristine results at the base of the staple, and also because it is such a unique trait and method of harvesting fleeces. I strive to roo as many of our sheep as I can in order to offer this special type of fleece to our handspinners.

|

| Nose kisses |